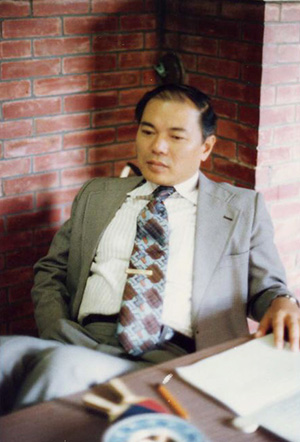

Kano Tsutomu (1935-2002)

Best known as the editor of The Japan Interpreter, a journal of social and political ideas in Japan, Kano Tsutomu is remembered as a master of social science/non-fiction Japanese-to-English translation. A voracious reader and versatile student of Japanese society and how it looks from outside, he devoted his life to interpreting Japan for English-speaking readers and to training translators. From early in his career, Kano was determined to “bolster the ability of Japanese to communicate their thoughts in English, and to increase the ability of English-speaking scholars to communicate Japanese ideas in their mother tongue” (written around 1967).

In a 1979 article entitled “The Alchemist,” he wrote:

Most important . . . is the ability to write smooth, logical, polished and natural English. The test of a translator in the deepest sense is whether or not he or she can transform Japanese writing into English that, with the exception of the author’s name, perhaps, gives not a hint of its foreign origin and still faithfully conveys what the author is saying.

Kano was mentor to numerous scholars and translators and a firm supporter of team translation:

I believe a competent team of a Japanese and a native speaker, whose powers of conceptualization and vocabulary are superior, can nonetheless produce translations of any Japanese materials, even those often considered untranslatable. In this I probably diverge from those who would like to preserve the Japanese order of phrase and sentence, style and vocabulary, for occasionally when handling a certain type of Japanese writing, the resulting translation sometimes appears to be so different from the original that the critic may wonder what sort of black magic went into its production. But if it is a skillful job, a closer look will show that it indeed says what the author wanted to say. In short, it conveys to the English reader exactly what the author told the Japanese reader. There is bound to be, especially in literature and poetry, some loss of style, nuance, the beauty of the original, but that can never constitute a reason not to translate a given work.

Concretely, the job of the translator is first to absorb the ideas and directional flow of what is written, grasp the main message and the supporting material, distinguishing among levels of importance. Then in the alchemy of the brain, he must process this understanding and conceptually rearrange ideas and facts in order of their logical role in English. This often means shifting material from the end of the Japanese paragraph to the beginning of the English, recombining elements of sentences to clarify their relationship, and making certain that illustrative points or secondary material appear where most effective.

. . . I believe—and I would not have stuck with the often thankless job of translating so long if I didn’t—that Japanese have much to offer the world in the intellectual realm, much that is neither imitation nor adaptation of Western ideas. Until now the intellectual resources of Japanese social science thinkers, both contemporary and past, have hardly been tapped for the world. The reasons lie largely in translation. The language is difficult, to begin with, but I think more important is a deeply-rooted, almost unconscious assumption, that Western thinking is world thinking. We are beginning to realize that this is a mistake, but in the case of Japan, nothing can be done about it until the quality of translation reaches a point where Japanese writing can be offered to other peoples in their own languages, and English is the first step.

(emphasis added—ed.)

Chronology

1935

Born in Obama, Fukui pref. April 13.

Father Seijiro worked for the Manchurian Railroad.

1948

Entered Shimogamo Junior High School, Kyoto.

1949

Father dies (Tsutomu age 14).

1951

Enters Rakuhoku High School, Kyoto.

1954

Enters Dept. of Philosophy, Kyoto University

1955

Joins Gakusei Hodo Renmei student federation (chairman, Shiraishi Akio), participates in editing of English-language magazine.

1956

Becomes third chairman of the Gakusei Hodo Renmei. Attends Student Bandung Conference in Indonesia. On Foreign Student Leadership Project (U.S. National Student Association-sponsored) scholarship, studies at University of Michigan (Ann Arbor).

1957

On return trip from Michigan, attends International Student Conference convened in Nigeria. After return from U.S., travels back and forth between Tokyo and Kyoto frequently. Involved as advisor to fourth chairman of Gakusei Hodo Renmei Inoue Masashi and 5th chairman Nishihara Masashi (later president of the Defense Academy [Boei Daigaku]).

1961

Participates in editing of Contemporary Japanese Political Abstracts of Selected Recent Works in Japanese sponsored by the Gotham Foundation Research Center (Chairman, Gaston J. Sigur). Establishes the Center for Japanese Social and Political Studies with the support of the Asia Foundation to publish Journal of Social and Political Ideas in Japan (JSPIJ). First issue published Spring 1963. Board of advisors: Matsumoto Sannosuke, Noda Fukuo, Okada Yuzuru, Oshima Yasumasa, Seki Yoshihiko. Editorial staff: Kano Tsutomu (executive secretary), Richard Miller (editorial adviser and translator), Nishihara Masashi (translation and research assistant), Bernard Key (translation assistant).

1962

Richard Miller, Bernard Key, John McCaleb join JSPIJ staff.

1964

JSPIJ changes its printing company from Dai-Nippon Insatsu to Komiyama Printing Company, where it was printed until the journal was suspended in 1980.

1965

Office moved from Yoyogi to Wakagi 11, later to Higashi 4-12-24 in Shibuya ward. Richard Miller returns to U.S. Robert Epp joins staff. Fund-raising activities in Japan and overseas begun to keep JSPIJ going.

1968

Introduced to Yamamoto Tadashi, with whom Kano collaborates on translation. Patricia Murray joins JSPIJ staff.

1970

Name of journal is changed to The Japan Interpreter: A Journal of Social and Political Ideas and publication continued. Fulbright scholars join journal staff on one-year stints: John Boyle (1969-70), Harris I. Martin (70-71), V. Dixon Morris (71-72), Frank Baldwin (72-73), Robert J. J. Wargo (73-74), James Huffman (74-75), David O. Mills (75-76), Ronald P. Loftus (76-77), Neil Waters (77-78), Mark D. Ericson (78-79), Herbert P. Bix (79-80), Anne Walthall (81-82). Board of Directors (at time of Vol. 6, No. 3):Nishi Haruhiko, Royama Masamichi, Nakayama Ichiro, Tobata Seiichi, Matsumoto Shigeharu, Matsuda Tomoo, Noma Seiichi, Okita Saburo, Kiyoko Takeda Cho, Saito Makoto, Nagai Michio, Minowa Shigeo, Hagihara Nobutoshi, Kano Tsutomu.

1972

Support begins from Japan Center for International Exchange (President: Yamamoto Tadashi); 1972-1975 Rockefeller Brothers grant. Support from Japan Society, New York provided in form of buy-up and distribution of journal in North America. Establishes Center for Social Science Communication, Inc. as a corporation through which to do translation on commercial basis and to be run parallel with not-for-profit, mainly academic, translation activities. Journal and Center staff: Patricia Murray, David Turner, Wayne Root, Tashiro Yasuko, Robert Ricketts, J. Victor Koschmann.

1973

Takechi Manabu and Robert J.J. Wargo join staff.

1974

Office moves from Shibuya Higashi 4-chome to Komae, Koadachi (later changed to Nishi-Nogawa).

1975

Participates as advisor for the Soka Gakkai International project to translate the Works of Nichiren. Advisor with Patricia Murray to the English-language newspaper, Seikyo Times, 1975-77.

1976

The Japan Interpreter receives the Mainichi Shinbun International Pubishing Culture Award [ck English] for The Silent Power (Simul Press). Lynne E. Riggs enters company; salary supported by JCIE.

1979

Translation Service Center founded as Asia Foundation project under leadership of James Stewart. Translation and editing of four articles weekly and about 200 op-ed pieces annually for distribution to newspapers overseas (mainly in U.S.), total of about 3,000 items in 1980-1995 period. Op-ed articles published monthly under title Japan Views.

1980

The Japan Interpreter ceases publication with Vol. 13, No. 1.

1981

Center office moves to Seijo, Setagaya-ku. Mother passes away.

1982

Joins editorial staff of PHP Institute English-language journal Entrepreneurship (1982-85).

1983

Publication of collection of essays by Kuwabara Takeo published by University of Tokyo Press under title, Japan and Western Civilization. Translation and editing of anthology of essays by Kuwabara Takeo with Patricia Murray. Becomes editorial advisor on staff of PHP Institute English-language magazine PHP Intersect (until 1996). Editor of Quest for Prosperity, autobiography of Matsushita Konosuke, published by PHP Institute in 1988.

1984

Translation of Not for Bread Alone, by Matsushita Konosuke.

1985

Publication of collected articles in column published 1985-1989 in PHP Intersect “As I See It,” essays on management philosophy by Matsushita Konosuke, in book form.

1988

Moved out of Seijo office and temporarily located CSSC office with newly established Center for Intercultural Communication in Komae.

1993

Involved in concept for Japan Foundation’s Japanese Book News quarterly; member of advisory board from No. 4 through No. 11.

1995

Opens office in Shinagawa, Takanawa.

1999

Travels to Taiwan with PHP Institute Managing Director Eguchi Katsuhiko to consult with then Taiwan president Lee Teng-hui about the translation of his autobiography into English. The Road to Democracy: Taiwan’s Pursuit of Identity published by PHP Institute.

2002

Dies July 5.